Sonata “1. X. 1905, From the Street”

I. Předtucha (Presentiment)

II. Smrt (Death)

Posterity shall forever be grateful for the good sense of the pianist that saved one of the most important piano works of the twentieth century from oblivion.

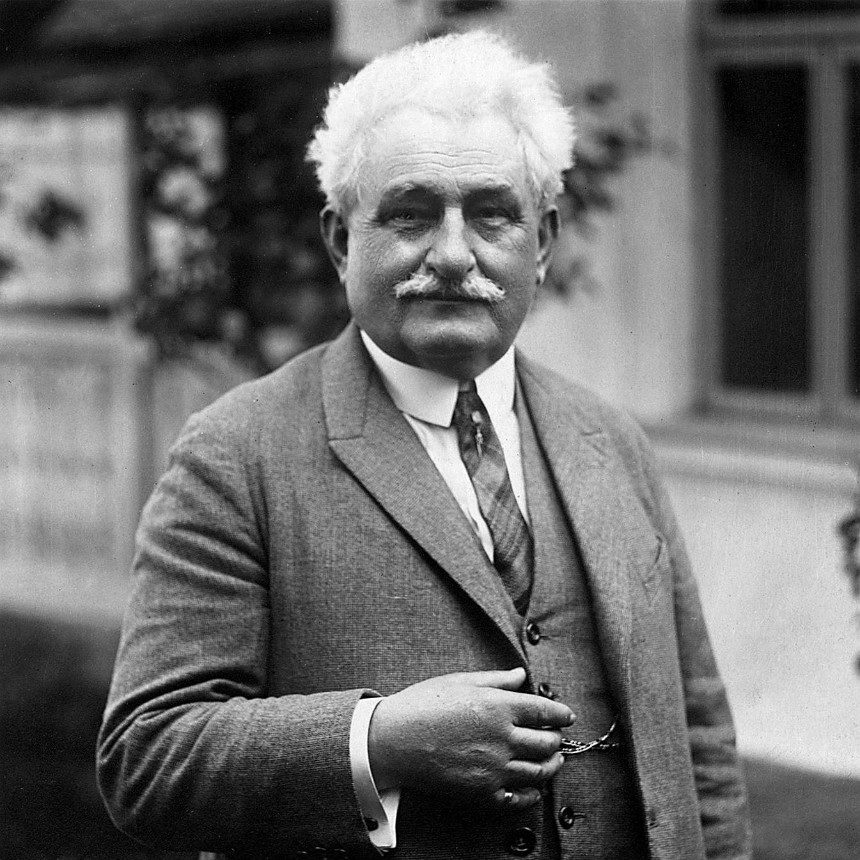

Janáček was an ardent Czech nationalist who, with his aggressively anti-German sentiment, had always resented the Austrian domination of his homeland. He was compelled to write “1. X. 1905, From the Street” (later referred to as a Sonata) by a tragic incident that happened on the date the title commemorates. During a demonstration supporting the foundation of a Czech-speaking university in Brno, tension arose between the German majority and the Czech minority of the city. During a skirmish that ensued, a Moravian carpenter, František Pavlík, was violently bayoneted to death by the forces of the ruling Imperial Government of the Habsburgs. Deeply affected by this event, Janáček conceived a three-movement work as a tribute.

On the day of the premiere while the pianist Ludmila Tučková was playing through the work to Janáček, the fiercely self-critical composer grew despondent and in a fit of self-doubt tore out the last movement, a funeral march, and threw it into the fire right before the pianist’s eyes. The concert went ahead, albeit with just the two-movement torso. Still dissatisfied, Janáček tossed the entire manuscript of the remaining work in the river Vltava. "And it floated along on the water that day, like white swans,” he later recalled, laden with remorse for his rash act. It wasn’t until 1924, almost twenty years later, that Tučková was able to pluck up the courage and confess to the seventy-year-old composer that she had made a copy of the two-movement Sonata. Remembering it with excitement, Janacek sanctioned its publication. Like its violent history, this searing work has the power even today to disturb and shock.

The volatile first movement “Presentiment” begins with a haunting melody, dislocated by sudden unsettling angular interjections. Much of Janáček’s music is peppered with these wild, obsessional and seemingly irrational outbursts, like willful aberrations. Spoken rather than sung, these agitated rhythmic patterns stem out of Czech speech. Janáček actively collected Moravian folk music and notated the speech melodies of people he encountered to use as material for his compositions. (He had, rather morbidly, scribbled down his daughter Olga’s last sigh on her deathbed.) A serene second theme recalls memories of a happier past.

In the second movement “Death” a chilling five-note phrase, a prayer perhaps, persists almost apathetically in a trance as if emotionally drained and numb with grief. The intensity imperceptibly builds as grief slowly grows into anger and torturous realisation, culminating in a terrifying climax. When the theme returns it is punctuated by painful pulsations in the bass, much like irregular beats of a heavy heart. The closing bars are utterly devastating in the profound hopelessness and quiet agony they convey; a faint glimmer of hope is extinguished like a brief candle by the final chord, a single toll of a funereal bell, signifying the end; nothingness engulfed in complete darkness.

Tony Chen Lin, 2019

You must be logged in to post a comment.